Cognitive dissonance over public employee pay is to detriment of Government expertise, policy delivery & staff motivation

COGNITIVE dissonance is impacting civil servant pay but always hampering government policy delivery.

Recently – on the one hand - we learnt that more than one in three senior DIT civil servants received performance-related bonus of up to £15,000 each (with an average pay out of £9,600). While on the other, three unions representing the rank-and-file of 200,000 public employees sought a judicial review over the government’s failure to consult staff on pay levels.

Early on in the research of the recent The Kakabadse Report (from Henley Business School), civil servant remuneration was one of the issues that took centre stage. Numerous senior civil servants reported the challenge they face filling posts due to the poor levels of pay on offer. Even senior civil servants highlighted the challenge of living in London on Civil Service pay: one Permanent Secretary stated, “I did not have my own house until I was 49 years old.”

Another frequently expressed frustration in The Kakabadse Report was the rapid turnover of civil servants, especially those who hold a particular expertise directly related to a project or programme of delivery. One key reason for the rapid turnover of talented individual civil servants is the prospect of an increase in pay and career progression. Being appointed to priority and high-profile projects allows the individual to rapidly learn how to address stretching challenges, which means they are better placed to be a favoured candidate for promotion within the Civil Service or for jobs in the private or third sectors.

Many civil servants also highlighted that for departments with multibillion-pound budgets, the levels of remuneration are low in relation to comparable responsibilities in the private sector. A considerable number reported joining the private sector, or intending to do so.

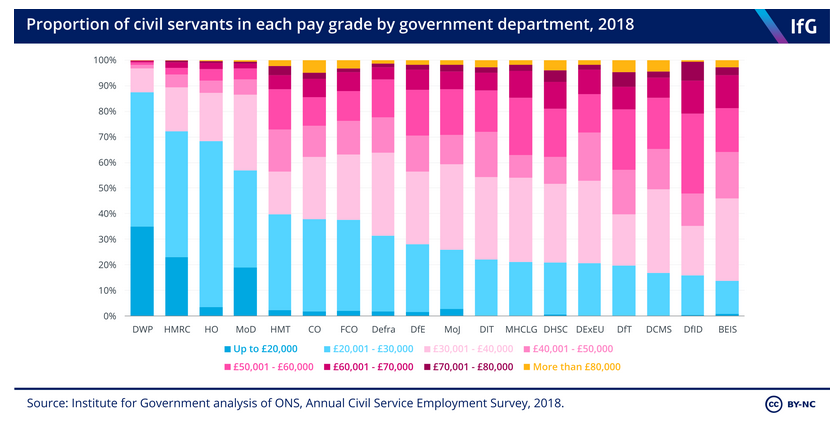

Not only do the comparatively poor and uncompetitive levels of civil service pay ensure talented individuals leave for the private sector. Worse still, the almost complete absence of joined up thinking by government across the sector compounds matters by perpetuating or increasing salary & rewards inequalities and differentials through its own inconsistently applied approaches to pay policy. It is particularly hard to justify paying such DTI bonuses for securing new trade deals when – looked at overall - the number of jobs created and secured by foreign investment fell by 7 percent.

If we are to continue to train and retain the brightest and best as well as motivate our public servants to rise to numerous current challenges in the service of our country, the Teresa May government urgently needs to get to grips with some corporate governance basics over its pay, remuneration and rewards policies.